In Episode 3 of the Personal Knowledge Management series using TheBrain, we started a review of specific sections of the daily note structure. Episode 2 discusses the reasoning behind setting up daily notes from the Journal Hub and includes the “one-note-per-day” and the “single .txt file” models.

Episode 4 is an optional feature of the daily note structure. However, I find value in tracking total time costs for projects, reading, time spent writing, studying, or a simple reminder to get off my butt and move more often. So here is a summary for those unfamiliar with the Pomodoro Technique.

First of all, the name Pomodoro is Italian and means tomato; now you, probably like me wonder what tomatoes have to do with time management? Well, it turns out that Francesco Cirillo, who developed the technique, figured out that if he could focus for ten minutes on a subject, he would become more productive. Eventually, he found that the cycle of 25-minutes focused work followed by 5-minutes of rest provided the most bang for his buck. His timer of choice was a tomato-shaped kitchen timer. The technique is simple enough, and here is a list I captured from Todoist’s productivity methods blog, The Pomodoro Technique. [1]

Get a to-do list and a timer.

Set your timer for 25 minutes, and focus on a single task until the timer rings.

When your session ends, mark off one Pomodoro and record what you completed.

Then enjoy a five-minute break.

After four Pomodoros, take a longer, more restorative 15-30 minute break.

The technique is highly effective, and the beauty is in the simplicity of alternating focused work with rest. Cirillo isn’t the first to discover this benefit, as Leonardo da Vinci also considered the “incubation” of his topics to be the most effective alternating between work and rest; however, “without periods of intense, focused work, there is nothing to be incubated.” [2] You must be doing the heavy lifting to make progress. The rest periods should be easy, mindless activities such as doing the dishes, taking out the trash, etc.

“Daily notes for July 26, 2022” copyright BrickBarnBlog2022

I include as part of my daily note structure a section on Pomodoro. In addition, I created a link to a separate page where all Pomodoros are captured by year [Pomodoro 2022]. Therefore, I can review every item on the list at a glance. For the most part, many entries are repetitive, i.e., journal entries, reading the news, etc. If, however, a project requires intensive computer work, especially if I expect it to be a long-term project covering months or years, I like to create a Pomodoro log for the specific project. I can capture the project log by week, month, quarter, or year, depending on my need for the information. The record itself is designed to grasp at a glance the number of 25-minute sessions I have spent on the project by period.

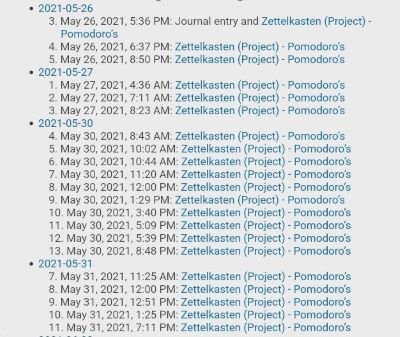

“Zettelkasten (Project) -Pomodoro’s Backlink Section” copyright BrickBarnBlog2022

For example, I studied the Zettelkasten methodology for about three years. In May 2021, I spent a considerable amount of time with the project; I could count the number of Pomodoro’s for the Zettelkasten (Project) that occurred on May 27, 2021, and times by 25 minutes. Three x 25 = 1h:30m (approximately, I don’t always get up and walk away when I have a train of thought going on in my head). I spent no time on the project on May 28 or the 29th. On May 30, 2021, I spent 10 Pomodoros at 25-minutes each = 5 hours, not including the longer breaks as seen between numbers 9 and 10.

“Daily Notes from May 27, 2021” copyright BrickBarnBlog2022

If I wanted to see what else I did on May 27, 2021, I could use the jump link and know that I worked on the Zettelkasten (Project) early in the morning, and then I went camping for Memorial Weekend at Cricket Mountain. Episode 5 of using TheBrain for Personal Knowledge Management will highlight my favorite section of daily notes, “Threads.”

Reference:

[1] [The Pomodoro Technique — Why It Works & How To Do It (todoist.com)](https://todoist.com/productivity-methods/pomodoro-technique)

[2] Gelb, M. (2004). *How to think like Leonardo da Vinci: Seven steps to genius every day*. New York, NY: Delta Trade Paperbacks. p.159.